Most of humanity now stands with its mouth open, aghast at the endless repetition of terrifying violence. Some people assume that new and better methods of killing will render ‘victory’ and that will solve the problem.

It won’t.

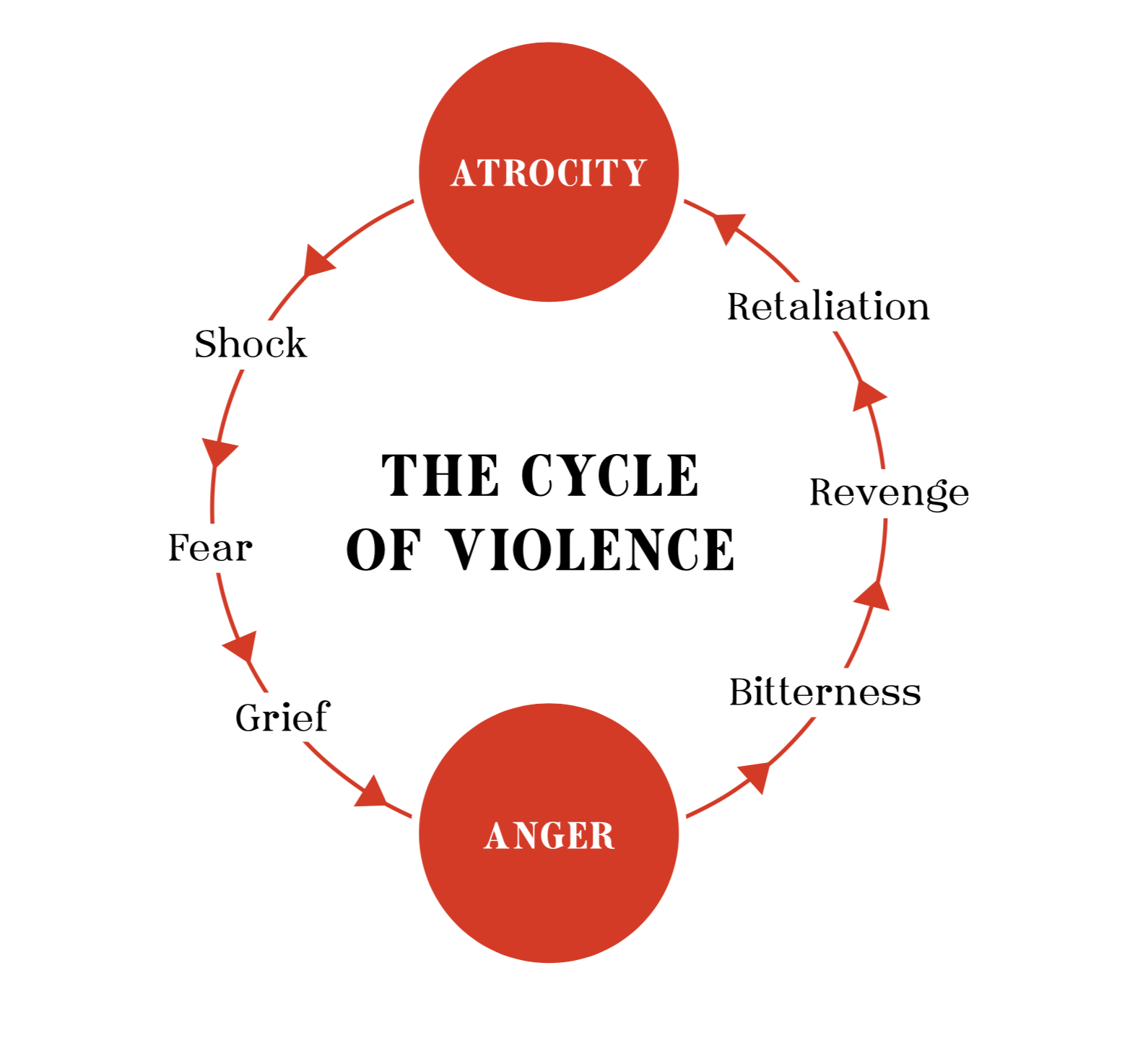

Why? Because the cycle of violence has not been interrupted.

The cycle begins with an atrocity. The result is shock, followed by fear, followed by grief. Then comes anger, and if nothing is done, anger becomes bitterness, demanding revenge and retaliation, resulting – of course – in another atrocity.

This article will show how this cycle of violence can be broken, why women must be included, how more women can be leading peace processes, and what we can do now to support them.

To break this cycle demands a different mentality and different skills, including the following:

Courage and understanding. Representatives of opposing sides who refuse to talk must be approached separately by intermediaries they trust, and who are able to liaise with each other. This is an extremely challenging process that takes deep courage, patience and profound understanding.

Demands and bottom lines. An initial first meeting should be secret, and often with only one or two representatives of either side, who will usually state their demands and bottom lines. This is likely to be contentious and fractious. But if this process can be handled with care, it may begin to suggest some possible advantages for either side, and they may agree to send more senior people to a further meeting.

Listening. If this meeting happens, the next round of talks must be guided by listening. Skilled mediators will insist that that includes listening not only to the demands of each side, but also to their deeper needs. Tensions will arise; skilled mediators will use compassionate communication to de-fuse tension fast.

Shared experience. Gradually, after many meetings, it becomes possible to share accounts of what has been experienced by either side, and for these to be heard compassionately, so that powerful feelings are less likely to feed the vicious cycle.

The short examples below do not begin to describe the immensely complex and demanding process of negotiation, but they suggest the advantages of using female skills in conflict prevention and resolution.

Why include women?

- Since women are not usually instigators of cycles of violence, they start from a different place, bringing less charged emotional baggage with them. They can be freer to empathise with others whom men may see only as enemies.

- Women tend to use intuition to enable parties to understand what’s needed in the moment. They come up with ideas and possibilities, that could “enlarge the pie, which men in power might not dream of.” (see Jonathan Powell)

- The male need for revenge is often triggered by shame and feelings of humiliation, including a failure to protect women whom they love. Revenge seems like the only way to alleviate these feelings and restore their sense of pride. Women can take a more long-term view and think more creatively about what might support a long-term peace.

- A balance of women in negotiating teams has been shown to help reach a peace deal that lasts longer. A statistical analysis of 182 signed peace agreements between 1989 and 2011 revealed that peace agreements where women are involved are 35% more likely to last for fifteen years.

- The ‘secret back channels’ – crucial in resolving many conflicts – can most effectively be carried out by women. (see Jonathan Powell) The ability to speak truth to power, without provoking hostility and violence, is invaluable.

So in practice, how could more women be leading peace processes?

First, we need to make known women’s track records in preventing or resolving armed conflicts and the principles they used:

In Northern Ireland, where sectarian killings had escalated to crisis levels, Betty Williams and Mairead Maguire co-founded the Community for Peace People, and mobilized over 10,000 Catholic and Protestant women to march and advocate for peace from 1974 – 1980, risking their lives to do so. They received the 1976 Nobel Peace Prize for their efforts to bring about an end to hostilities. Principle: enable people on the ground from dissonant communities to meet, talk and march together to show their leaders that they unite for and insist on a peaceful future.

In Liberia, after a 14-year civil war, Leymah Gbowee united Christian and Muslim women in an interfaith movement, the Women of Liberia Mass Action for Peace. The women acted as intermediaries between Charles Taylor and rebel leaders and even and even carried out sex strikes to stop the men from fighting. Their efforts laid the foundations for Ellen Johnson Sirleaf to become the first female African head of state. In 2011, both Gbowee and Johnson Sirleaf were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. Principle: unite in an interfaith movement and prevent male negotiators from leaving talks until agreement is reached.

In Kenya, when violence erupted after disputed elections in 2007, Dekha Ibrahim Abdi asked the 60,000 members of a women’s organisation to report what they saw on cell phones. The information pouring in enabled them to plot not only the ‘hot spots’ of the violence but also the ‘cold spots’ – to know where people were running to for protection. They then developed strategies for each spot, with the help of trusted local leaders. In less than 3 weeks these strategies brought the violence under control. Principle: use female networks plus latest tech to map the spread of violence, enabling strategies to bring violence under control to prepare for a planned peace.

In the UK in 1981 the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp was set up to protest against nuclear cruise missiles being placed at the RAF camp there. A year later, 30,000 women joined hands around the base to Embrace the Base with their children. The courage of the Greenham women hit the headlines again when a small group climbed the fence to dance on missile silos on New Year’s Day 1983. The media attention surrounding the camp inspired people across Europe to create other peace camps. The last missiles left the base in 1991. Principle: combine women’s courage with their determination to rid the world of cruise missiles; it may take ten years but works in the end.

In the Philippines in 2014, when Miriam Coronel-Ferrer led the government’s negotiating team, she was the first woman to sign a major peace deal. This treaty provided a framework for ending the 40-year conflict between the Filipino government and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) a rebel group that hoped to create an independent Muslim majority state. Women made up 33% of that negotiating team and 25% of the signatories. Principle: when women lead and make up more than one third of those negotiating a peace treaty, it will produce agreements that last.

In Colombia a peace treaty was signed in 2016 to bring an end to the 50-year conflict between the government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces (FARC). The conflict had claimed over 200,000 lives and had displaced about 7 million people. Finally, when women made up 20% of the government team and 43% of the FARC negotiating team, it was the first time a gender sub-commission had been included in a peace negotiation. The final treaty included a range of provisions for women. Principle: include a gender sub-commission in every peace negotiation, for future women’s rights and protection from violence.

Afghanistan is perhaps the last place you’d expect a young woman aged 14 to attend international peace talks, after the Taliban rose to power. Zuhra’s dedication to peace and to her country then enabled her to become a powerful program director—currently the only woman leading a network of civil society organizations in Afghanistan. Through her leadership and bravery, Search for Common Ground is now the backbone of the largest network of civil society activists in the country, involving over 100 organizations. Principle: individual courage can enable women to become leaders even under the most oppressive regimes.

Next, in conflicts we know of, we need to put forward names of skilled female negotiators to lead the peace process, including for example:

Catherine Ashton, British Labour politician ex CND, who served as the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy and First Vice President of the European Commission from 2009 to 2014. Negotiated truce in Serbia/Kosovo,

Mary Robinson, first woman President of Ireland 1990 to 1997, former UN High Commissioner for Human Rights; chair of The Elders; a passionate advocate for gender equality, women’s participation in peace-building.

Lehmah Gbowee and Ellen Johnson Sirleaf helped end the Liberian civil war by organising hundreds of women to stop male negotiators leaving peace talks. They were awarded the 2011 Nobel Peace Prize “for their non-violent struggle for women’s right to full participation in peace-building work.”

Margot Wallstrom, Deputy Prime Minister of Sweden and Minister for Foreign Affairs from 2014 to 2019 and Minister for Nordic Cooperation from 2016 to 2019.

Christiana Figueres, appointed Executive Secretary of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change in July 2010, steadily rebuilt the global climate change negotiating process leading to the 2015 Paris Agreement, widely recognized as a historic achievement.

Nadia Murad, member of the Yazidi minority in Northern Iraq. By recounting the atrocities perpetrated against her, Nadia helped ensure that future generations of young women do not become victims of sexual violence in war. She won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2018.

Jacinda Ardern, became the youngest PM of New Zealand in 2017. When she defused racism after a terror attack in Christchurch, the Guardian wrote: “Ardern has moulded a different consensus, demonstrating action, care, unity. Terrorism sees difference and wants to annihilate it. Ardern sees difference and wants to respect it, embrace it and connect with it.”

So, what can we do now?

It may be that reading this, you feel inspired to research any conflicts you care about and perhaps put forward names of skilled female negotiators to lead the peace process.

You may like to wake colleagues to notice the gender of leaders in armed conflicts. Count how many women you can see. Do the same for those around peace tables. Make these numbers known. The more we wake up to the absence of women in negotiating on war and violence, the more likely we are to have conflicts resolved.

If you prefer to work at a more local level, have a look at conflicts in your area, in your workplace, in your kids’ school. Get advice, read up on similar disputes. Take your courage and your phone in your hands, talk to a few competent imaginative women who you feel would be able to put forward proposals for talks. Gather them around a kitchen table somewhere. Listen. Make notes. Form a plan. Soon you’ll have a team of competent practical women to suggest what could be done, and how. Set it out in a good presentation. See what happens. If you get stuck, tell your local media. This is how we learn. It’s how most of those women in the stories above got going. Much better for our health than wringing hands.